“It was like every night was Halloween,” says Smith, remembering two girls wearing hazmat suits.

Smith’s photos are a document of a different era, and could be seen as a timely repost. As Honey Dijon notes in the book: “Today, to get past the red rope you just have to pay, but back then you had to have a look or a vibe or a witty repartee – there had to be something about you – to pass through that door.” For some that might sound like a lot of pressure. “A little bit,” says Smith, “but it also adds this element of fun,” something she thinks “is sorely missing in our culture.” It made going out “an event,” she says.

It also sounds like a sartorial challenge for someone more used to dressing down. “For me, it was an education,” she says. “It took me a couple of months to figure out that I needed to be noticeable in some way, but not competitive with people.” Her “costume” – her word – evolved. “It ended up being a black strapless dress with fingerless black lace gloves and these high heels that I got from Barneys on sale, which I wore to death.”

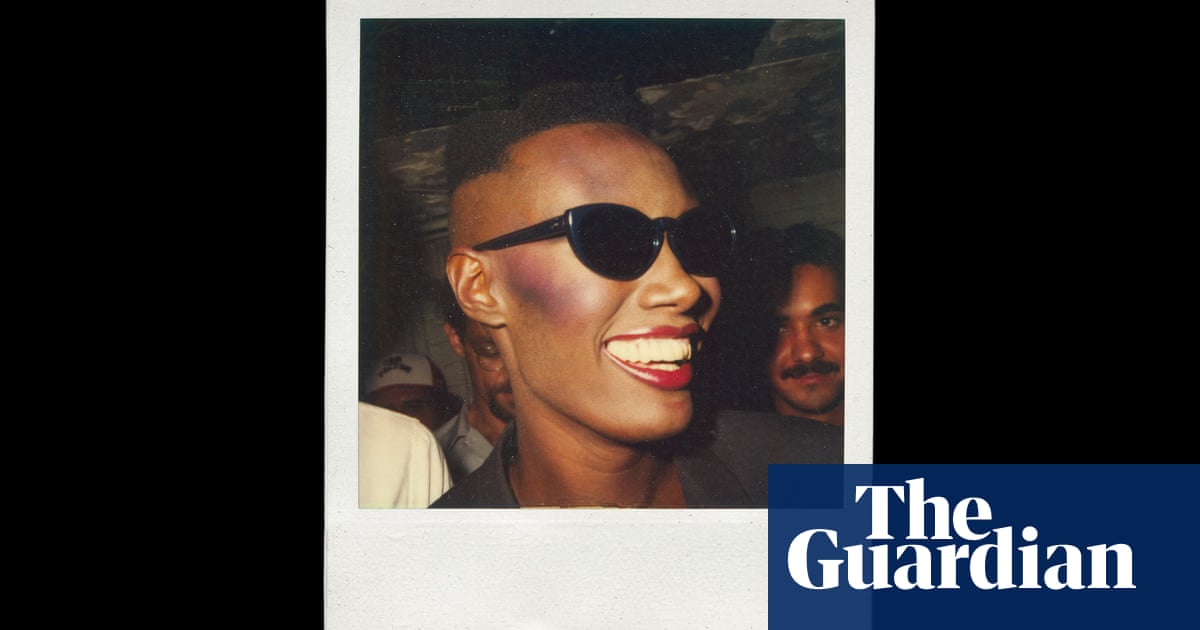

Innocuous, relatively speaking, but also not nothing, Smith’s chosen look probably helped her to get the shots that she did. There’s one of Debbie Harry in a red and yellow stripey T-shirt with pink eyeshadow, and another of David Bowie delicately tucking his chin to give a profile shot. “I don’t remember a lot about that. But I did ask him and then he just gently turned his head. It wasn’t like he wanted to get away from me. It was like: ‘Oh, look at this.'” In the book she recounts her 3am encounter with Grace Jones. “When I walked up to her and raised my camera … she looked at me for a split second, slipped on her sunglasses, then smiled. The flash went off and she whispered, ‘Thanks, love,’ – then strode on to the dancefloor.”

There is a lingering sadness to the pictures, too. A record of the life-affirming creative scene in a city bubbling with talent and energy, many of the photographs capture people who would go on to die during the Aids epidemic that would soon sweep the city. “A lot of these people are no longer with us. A lot of them,” says Smith.

If the outfits in the clubs were an education to Smith, it sounds like they were also an education to people outside the scene. “People would buy a T-shirt in the basement of the Ritz about a band and they would rip it up. And then two weeks later people would be buying ripped up T-shirts from shops on Madison Avenue … The fashion that was going on there had legs.”

Smith was 28 when she walked into the Ritz and set out her stall selling quickfire portraits to partygoers for $3 a pop. Now 73 and a tai chi teacher, she thinks some of the sartorial brilliance may have been a response to the repressive politics of the day. “It was the Reagan years. New York was kind of a gritty place, and you walked into the clubs and there was this celebratory feeling and people were dressed up.”

She thinks the individuality on display then isn’t happening now. ” Pero, para bien o para mal, eso podría estar a punto de cambiar. “No es una razón para pasar por este horrible [tiempo]”, pero si algo bueno surge de ello, espera que “haya otra explosión de creatividad”.

Camera Girl de Sharon Smith ya está disponible, publicado por Idea